What are DICOM files and why does their structure matter?

DICOM files are the backbone of medical image data exchange outside of network environments. Whether we’re talking about patient CDs, USB drives with exams, or email attachments with radiological images, we’re dealing with DICOM files — and understanding their internal anatomy is essential for anyone working with imaging system integration.

In daily practice, most professionals interact with these files without giving a second thought to what happens under the hood. But if you’ve ever had to deal with a patient CD that “won’t open” on another system, or tried to import data that simply wasn’t recognized by the receiving PACS, the problem likely lay in the file structure. For a complete overview of the DICOM ecosystem, check our comprehensive guide to DICOM in clinical practice.

Anatomy of a DICOM file: from preamble to data object

Every DICOM file follows a rigorously defined structure specified in parts PS3.10, PS3.11, and PS3.12 of the standard. This structure consists of four sequential sections, and understanding each one saves a lot of headaches.

Preamble and DICM prefix

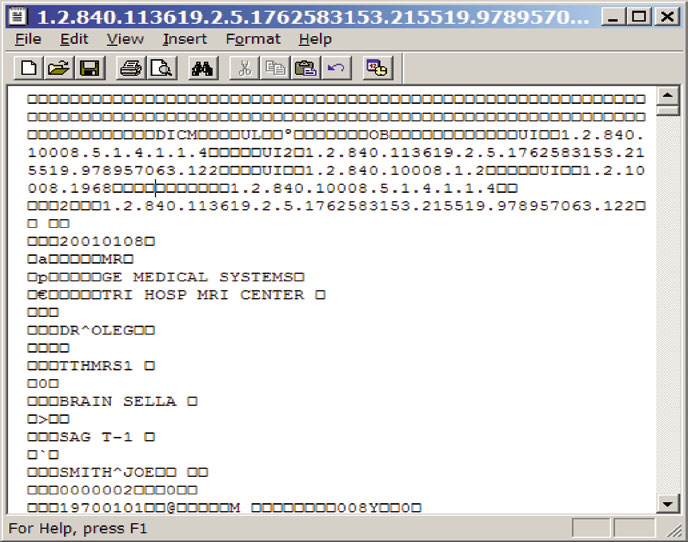

The first 128 bytes of any DICOM file constitute the preamble. The DICOM standard doesn’t define specific content for this area — each application can use it as it sees fit. In practice, most software simply fills these 128 bytes with zeros. Right after that, in bytes 129 through 132, we find the four uppercase letters D I C M: the prefix that unambiguously identifies a DICOM file.

This is, in fact, the only truly reliable method for identifying whether a file is DICOM or not. Forget about the “.dcm” extension — it’s merely a convention, and the standard itself oscillates between prohibiting and requiring it in different contexts. If you’re writing software to identify DICOM files, skip the first 128 bytes and verify the DICM prefix. Period.

Group 0002: file meta information

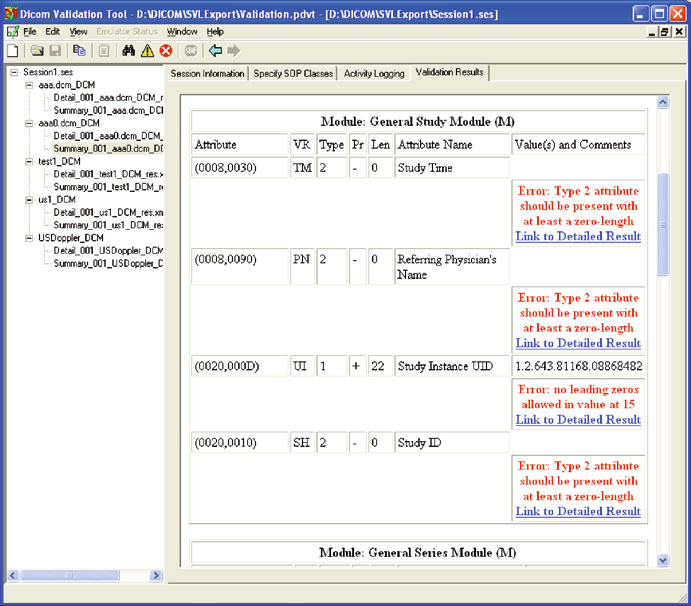

Starting at byte 133, we find the File Meta Information — a set of DICOM attributes belonging to group 0002. These elements are always encoded with explicit VR, regardless of how the actual data object is encoded. Among the most important attributes are:

- Media Storage SOP Class UID (0002,0002): identifies the type of stored object (CT, MR, US, etc.)

- Media Storage SOP Instance UID (0002,0003): unique instance identifier

- Transfer Syntax UID (0002,0010): defines how the data object is encoded — arguably the most critical attribute in the entire group

- Implementation Class UID (0002,0012): identifies the implementation that created the file

In my experience, the Transfer Syntax UID is where many interoperability problems begin. In DICOM network communication, the Transfer Syntax is negotiated during association establishment. In files, it’s recorded in the header — and if the receiving software doesn’t interpret it correctly, it simply can’t decode the images.

The data object

After group 0002, we find the actual DICOM object — the same data structures used in network communication. Group numbering starts at 0008, making it easy to identify where meta information ends and clinical data begins. As discussed in our post about DICOM objects and data encoding, VR encoding defines how each attribute is interpreted.

A critical consideration: group 0002 always uses explicit VR, but the data object may use implicit VR, depending on the Transfer Syntax indicated in field (0002,0010). Software that doesn’t make this switch during reading will fail. For this reason, the DICOM standard recommends explicit VR throughout the entire file — even though DICOM’s default Transfer Syntax is Implicit Little Endian.

DICOMDIR: the index that organizes (and complicates) everything

The DICOMDIR is a special DICOM file that functions as an index — a miniature database listing all DICOM files present in a given directory. It organizes information into four hierarchical levels: Patient → Study → Series → Image.

When you insert a DICOM CD into a PACS workstation, the software typically reads the DICOMDIR first to present the list of patients, studies, and series contained on the media. Patient names, study dates, modalities — all extracted from the selection keys stored in the DICOMDIR.

Internally, the DICOMDIR uses an SQ sequence (0004,1220) that contains all directory records. Each entry holds two types of data: selection keys for searching (such as modality and patient name) and Basic Directory Information Object entries (group 0004), which store file IDs and relationships between records.

Practical problems with DICOMDIR

In practice, DICOMDIRs present significant limitations. There are at least three concrete reasons to be skeptical:

1. Questionable utility. Any well-designed DICOM program should scan all files in a given folder, identifying those in DICOM format. Even a full DVD can be scanned fairly quickly. For PACS import or viewing — the two most common use cases — DICOMDIR adds negligible efficiency.

2. Fragility. When we export data to removable media, users inevitably copy, rename, and reorganize files. Any of these actions invalidates the DICOMDIR. If the receiving software depends solely on it for import, results will be incorrect. There are even dedicated tools for fixing invalid DICOMDIRs — which by itself demonstrates the scale of the problem.

3. Maintenance complexity. The DICOMDIR needs to be updated every time any file in the directory changes. On write-once media (CD-R), it must be the last file recorded to accurately reflect the contents.

File services and DICOM application roles

The DICOM standard defines five media services for file operations: M-WRITE (create), M-READ (read), M-DELETE (delete), M-INQUIRE FILE-SET (query space), and M-INQUIRE FILE (query creation date/time). Based on these services, any Application Entity takes one of three roles:

- File Set Creator (FSC): creates the DICOMDIR and DICOM files

- File Set Reader (FSR): reads only, without modifying any files

- File Set Updater (FSU): can read, create, and delete — in practice functions as FSC + FSR with M-DELETE capability

The comparison with DICOM network communication is instructive. In the network model, Application Profiles are negotiated during association establishment. With files, this negotiation simply doesn’t exist — profiles must be compatible from the start. If one application writes MR images and the other expects CT, there’s no friendly error mechanism. This led the standard to define extremely detailed Application Profiles, as explored in our article on DICOM fundamentals: objects, communication, and data.

DICOM file security: encryption and signatures

A fundamental difference between transmitting DICOM objects over a network and exchanging them as files is the scope of security risks. Intercepting network messages requires specialized skills; copying, deleting, or modifying a file is something anyone can do.

The secure DICOM file format provides three protection properties:

- Confidentiality: the entire file is encrypted and unreadable without the correct key

- Origin authentication: certificates and digital signatures identify who created or modified the file

- Integrity: checksums and signatures prevent undetected alterations to data like patient name or report date

In practice, adoption of secure DICOM files remains quite limited. Few PACS software products implement this feature, and the standard definition remains superficial. If data security on removable media is a concern — and it should be, considering regulations like HIPAA and GDPR — the best strategy remains eliminating physical media from the process entirely.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Over years of DICOM integration work, certain problems recur with concerning frequency:

1. Relying on filename for identification. The “.dcm” extension is not standardized. Many implementations use SOP UIDs as filenames, resulting in long, potentially problematic strings. Always identify DICOM files by the DICM prefix in the header.

2. Not handling the VR switch between header and data. Group 0002 is always Explicit VR. If the data object’s Transfer Syntax specifies Implicit VR, the software must make this switch. This is one of the most frequent bugs in DICOM readers.

3. Using backslashes in File IDs. The File ID component separator uses backslash (\), which is also the DICOM wildcard character for “logical OR.” Splitting filenames by backslash into separate components is one of the most widespread bugs. Use forward slashes (/) instead.

When NOT to use DICOM media

Physical DICOM media exchange should be avoided whenever possible. Scenarios where DICOM networking or web solutions should be preferred:

- Frequent inter-institutional transfers: VPN networks with DICOM C-Store are infinitely more efficient than burn/ship/import CD cycles

- External referring physicians: web teleradiology solutions provide immediate access without requiring installed DICOM software

- Any scenario where re-sending is likely: burn a CD, mail it, discover thin slices are missing, re-burn… this cycle is unproductive and costly

The concept of medialess has gained traction in the community: completely eliminating CDs and DVDs from data exchange workflows. If you can adopt this approach, do it. No media = no media problems.

For a deeper analysis of DICOM network communication as an alternative to media exchange, see our article on DICOM communication: SOPs, DIMSE, and networking in practice. To understand the encoding of objects stored in these files, check our post about DICOM objects and data structure.

The future: DICOM storage beyond current limitations

The current DICOM media storage model is, frankly, excessively detailed in aspects it shouldn’t control — like boot sectors and media-specific filename rules. At the same time, it leaves gaps where flexibility would be most useful.

An interesting proposal would be creating a DICOM packaging utility — something like a “DICOMPack” that works similarly to ZIP and RAR archivers but with medical imaging-specific features: JPEG2000 or JPEG-LS compression (far more efficient than ZIP for image data), encryption support, file splitting, and even built-in anonymization. This approach would eliminate media-specific dependencies, making data exchange more portable and secure.

The DICOM standard already allows ZIP for compressing DICOM folders (Annex L of PS3.11) and archiving file sets (Annex V of PS3.12), but with restrictions that limit practical utility — predefined names, only one file set per archive, no image-specific compression. The natural evolution involves abstracting the media layer and focusing on intelligent packaging functionality.

Until these improvements materialize, the practical recommendation is clear: invest in network infrastructure and remote access solutions, reserving physical media only for situations where there’s truly no alternative.