In This Article

What Is DICOM and Why It Still Rules Medical Imaging

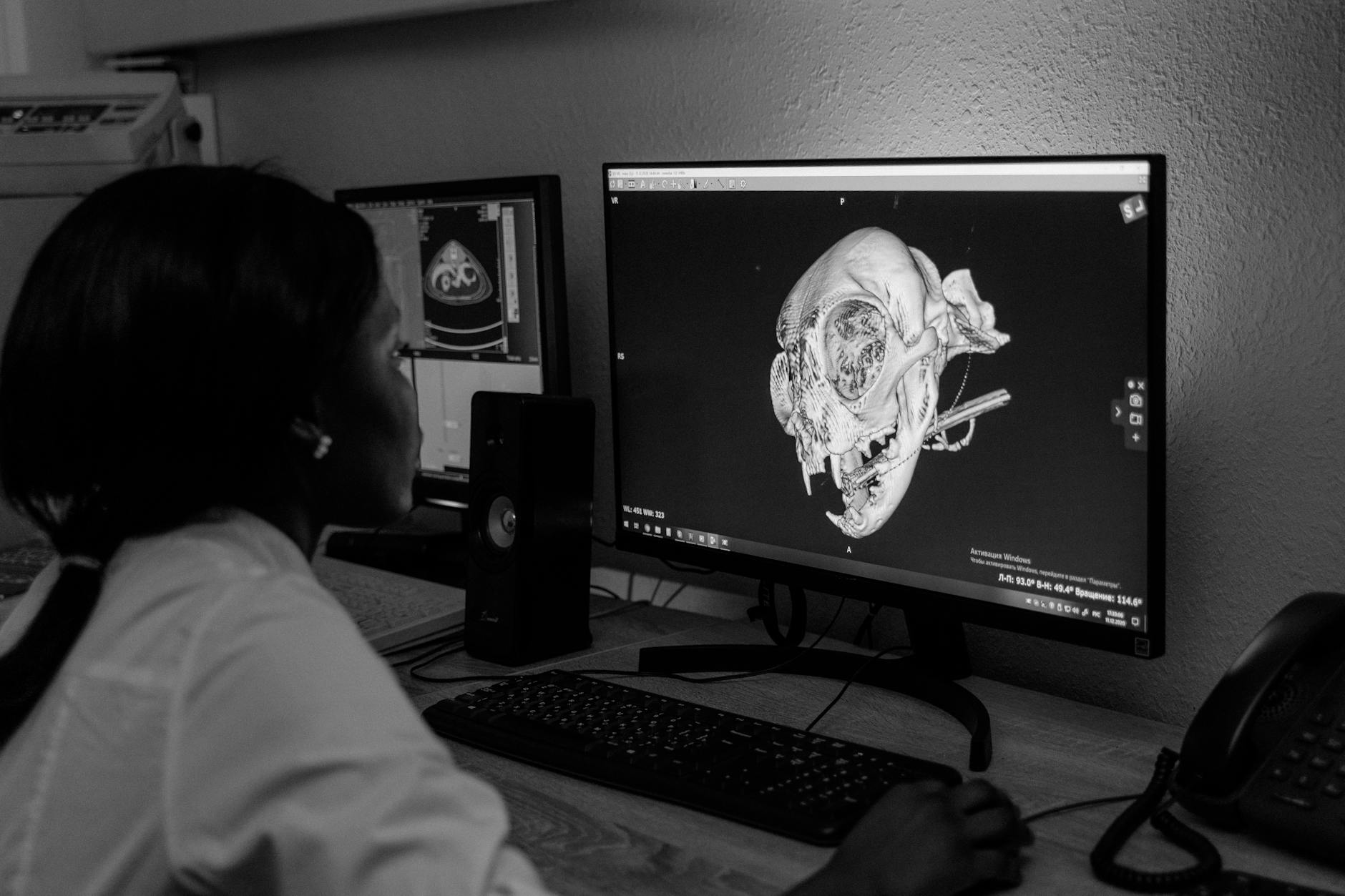

DICOM is not just a file format. That remains the most persistent misconception among professionals entering the digital radiology world. In reality, the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine standard is a comprehensive data transfer, storage, and display protocol designed to cover virtually every functional aspect of contemporary digital medicine.

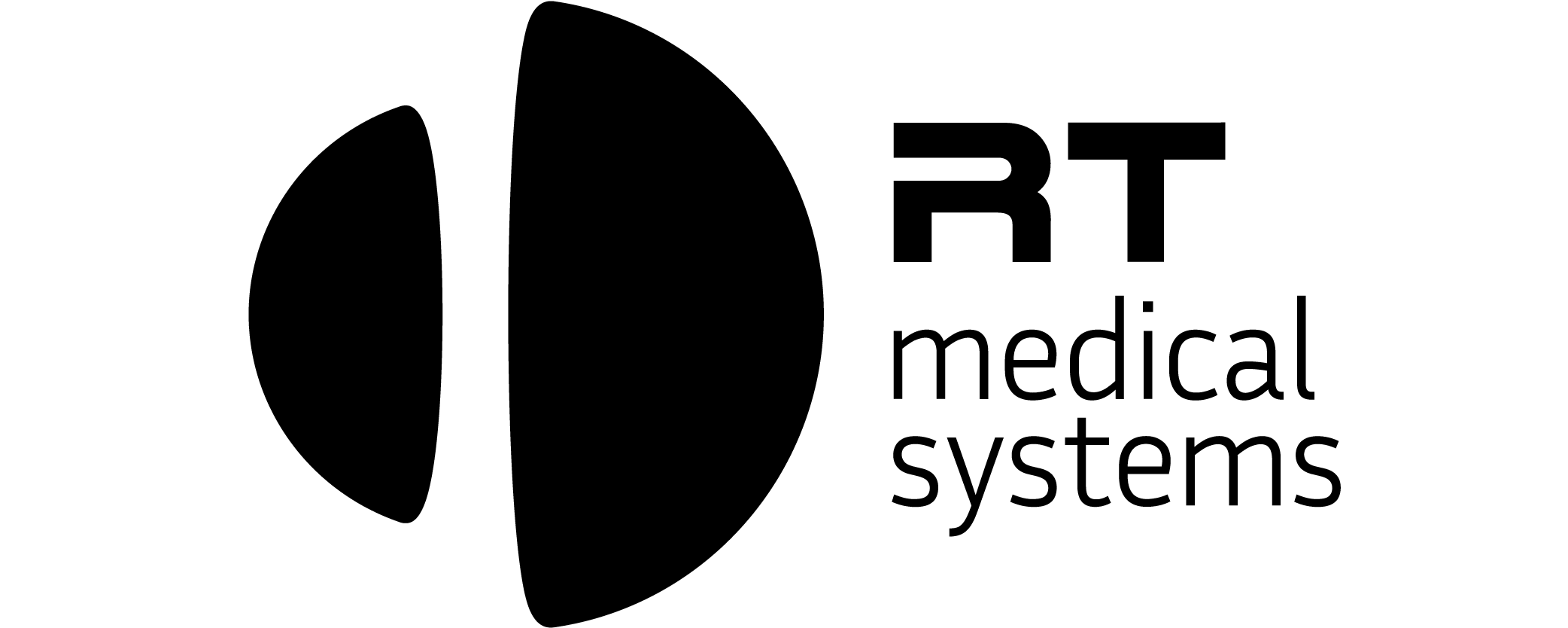

Conceived in 1983 by a joint committee between the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA), the standard evolved from a simple magnetic tape recording specification to an ecosystem that underpins the entire medical imaging chain. Today, every digital acquisition device — CT scanners, MRIs, ultrasound machines — produces DICOM images and communicates through DICOM networks. For a comprehensive overview of how this standard integrates into clinical practice, check our complete guide to DICOM in clinical practice and imaging system integration.

What makes DICOM irreplaceable? Three pillars: exceptional diagnostic quality (support for up to 65,536 grayscale levels, compared to 256 in conventional JPEG), complete clinical metadata encoding through more than 2,000 standardized attributes, and precise device functionality definition through Conformance Statements.

DICOM Information Model: How Clinical Data Is Structured

DICOM views real-world entities — patients, studies, devices — as objects described by attributes. These definitions are formalized in Information Object Definitions (IODs). A patient, for example, is represented by attributes such as name, ID, sex, age, and weight, capturing all clinically relevant information.

This object-oriented approach might seem abstract, but it solves a concrete problem: when a CT scanner sends an image to the PACS archive, both devices need to agree on what constitutes “a CT exam” — which fields are mandatory, how to format dates, how to uniquely identify each series. IODs provide that contract.

Information Hierarchy

DICOM data follows a four-level hierarchy: Patient → Study → Series → Image. Each level has a unique identifier (UID) that ensures traceability. In practice, duplicate Patient IDs or conflicting study UIDs are among the most frequent causes of images being “lost” or erroneously merged in the PACS.

IODs are composed of Modules (reusable data blocks) that group into Information Entities (IEs). This modular architecture allows different modalities to share common modules — like the Patient Module — while adding modality-specific modules for CT, MR, or ultrasound data.

VRs and Data Dictionary: The Grammar of DICOM

If IODs define what to store, Value Representations (VRs) define how to store it. DICOM specifies 27 VR types that function as the standard’s grammar. There are VRs for short text (SH, LO), long text (ST, LT, UT), dates and times (DA, TM, DT), text-format numbers (IS, DS), binary numbers (SS, US, SL, UL, FL, FD), person names (PN), entity identifiers (AE), and unique identifiers (UI).

Each VR has specific length and character encoding rules. An AE (Application Entity Title) field, for example, accepts a maximum of 16 characters — a limitation that, surprisingly, still causes issues when administrators attempt to configure overly descriptive device names.

Standard and Private Data Dictionaries

The DICOM Data Dictionary catalogs all standardized attributes with their tags (group, element), VRs, multiplicity, and description. But manufacturers frequently need to store proprietary data — and for that, the Private Data Dictionaries mechanism exists. Tags with odd group numbers are reserved for private use, allowing each manufacturer to extend the standard without conflicting with official attributes.

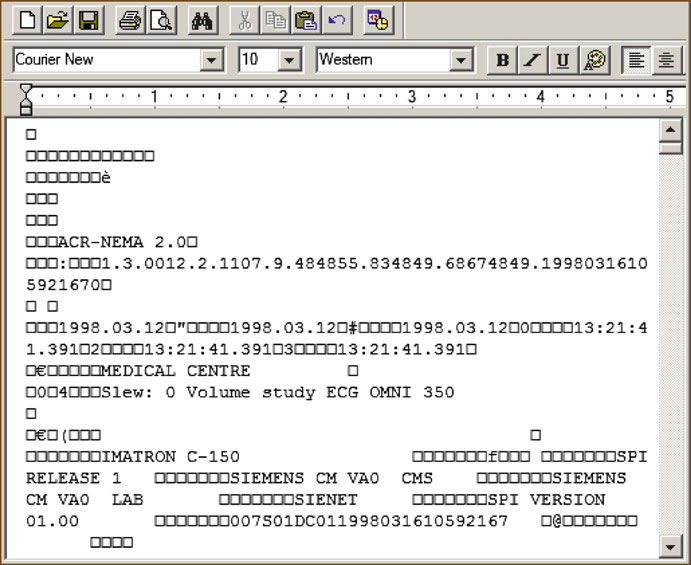

DICOM Object Encoding

In practice, a DICOM object is an ordered sequence of Data Elements, each composed of a tag (4-byte numeric identifier), the VR, the value length, and the value itself. Elements can be nested through the SQ (Sequence) type, enabling complex hierarchical structures — such as a list of scheduled procedures within a worklist.

DICOM Communications: SOPs, DIMSE, and Associations

Devices on the DICOM network are called Application Entities (AEs), identified by an AE Title, IP address, and port. All communication follows the Service-Object Pair (SOP) model: a service associated with the type of data it processes.

DICOM defines clear roles: whoever requests a service is the Service Class User (SCU), and whoever provides it is the Service Class Provider (SCP). A CT scanner storing images to the PACS acts as a CT Storage SCU, while the archive acts as a CT Storage SCP. The same device can switch roles — when the archive needs to print, it becomes a Print SCU to the DICOM printer.

Fundamental DIMSE Services

Services are implemented through the DIMSE (DICOM Message Service Element) protocol, which offers operations such as:

- C-Echo: the DICOM “ping” — verifies connectivity between two AEs

- C-Store: transfers objects (images, reports) for storage

- C-Find: queries the study/patient catalog in the archive

- C-Move / C-Get: retrieves images stored in the PACS

- MWL (Modality Worklist): synchronizes the RIS worklist with the modality

The difference between C-Move and C-Get is a frequent source of confusion. C-Get transfers images directly to the requester, while C-Move instructs the server to send images to a third-party AE — useful when the viewing workstation is not the one that performed the query.

Association Establishment

Before any data exchange, two AEs must negotiate an association. During this “handshake” phase, they exchange Presentation Contexts — combinations of Abstract Syntax (the SOP to be used) and Transfer Syntax (how data will be encoded: Little Endian, Big Endian, compressed). If no compatible context is found, the association is rejected.

In my experience, most DICOM connectivity failures are resolved by checking three things: correct AE Title, open firewall port, and compatible Transfer Syntax on both sides.

DICOM Media: Files, DICOMDIR, and Security

The DICOM file format follows a specific structure: a 128-byte preamble, the “DICM” prefix, a meta-information group (Group 0002) with the file’s Transfer Syntax, and finally the data object. This format allows any software to unequivocally identify a DICOM file.

DICOMDIR functions as a hierarchical index for removable media (CDs, DVDs, USB drives). It maps patients, studies, series, and images in a navigable structure without requiring a database. Although it might seem outdated in the cloud era, DICOMDIR remains essential for transferring exams between institutions without direct network connectivity.

PACS Storage

PACS can store DICOM data in three ways: file-based (files on the filesystem), database-based (binary data in the database), or mixed models (metadata in the database, pixel data in files). Each approach involves performance versus backup simplicity trade-offs that must be evaluated according to the institution’s volume.

Security and Anonymization

DICOM security is, historically, a weak point of the standard. Traditional DICOM networks operate without encryption, and the protocol itself was designed before modern privacy concerns. Anonymization of DICOM data — removal or replacement of identifiable attributes (name, date of birth, IDs) — is regulated by PS3.15 and Supplement 142, but in practice requires attention to details like “burned-in” data in images (annotations rendered into pixels).

The standard supports TLS for network communications and secure file formats with encryption, but adoption remains limited. Institutions dealing with teleradiology or multicenter research should prioritize VPNs and rigorous de-identification processes.

Common Errors and DICOM Limitations

After years working with DICOM integration, certain error patterns repeat with impressive consistency. Recognizing them can save weeks of troubleshooting.

| Error | Typical Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Images don’t reach PACS | Incorrect AE Title or blocked port | Check Conformance Statement and network config |

| Studies erroneously merged | Duplicate Patient ID across patients | Implement MPI or ID reconciliation |

| “Corrupted” image display | Unsupported Transfer Syntax in viewer | Check compression (JPEG2000 vs JPEG Lossless) |

| Empty worklist on modality | HL7/MWL integration failure | Validate field mapping between RIS and modality |

When DICOM Is Not Enough

Despite its robustness, DICOM has real limitations. The standard does not natively manage clinical workflow (IHE exists for that), does not replace HL7/FHIR integration between HIS/RIS, and its native security model is insufficient for internet-exposed environments. Devices labeled “DICOM-Ready” frequently mean that DICOM functionality is a separate paid option — a detail that can surprise unprepared administrators.

Mini Case Study: PACS Migration

A diagnostic imaging clinic with 3 CT scanners, 2 MRIs, and 15 workstations decided to migrate from a legacy PACS (10 years old) to a modern solution. The DICOM inventory revealed that one CT scanner supported only JPEG Lossless as compression Transfer Syntax, while the new PACS expected JPEG 2000. Result: 40% of historical images needed transcoding — a process that took 3 weeks for an 18 TB archive. The lesson: validate compatible Transfer Syntaxes before signing the migration contract.